Art and collections

We care for one of the world's largest and most significant collections of art and heritage objects. Explore the highlights, our latest major exhibitions, curatorial research and more.

You may not expect to see pictures of Chinese gardens and landscapes on the walls of a British country house. Yet, we care for the largest collection of historic Chinese wallpapers on permanent public display in the world.

When trade between Asia and Europe grew in the 17th century, Europeans developed a taste for Chinese art and design. By the mid-18th century, Chinese wallpapers had become a highly fashionable ingredient of British country house interiors.

Eighteen historic houses in our care contain examples of Chinese wallcoverings. They include woodblock-printed wallpaper, collages of Chinese prints and paintings, and fully hand-painted wallpaper.

Some of the historic woodblock prints used in these wallpapers now only survive in European houses, even though they were originally made for the Chinese market.

In the early 17th century, English and Dutch merchants formed so-called East India Companies to spread the risk of trading with Asia. The products they commissioned from Asian suppliers reflected European taste. There was strong demand in Europe for Indian chintz, Japanese lacquer and Chinese porcelain.

Alongside the demand for Chinese products, at this time there was also great respect and admiration for Chinese civilisation. Jesuit missionaries, trying to convert Chinese people to Christianity, produced enthusiastic books about the country and its people.

These were popular in Europe and helped create an image of China as an ancient, stable, wealthy and virtuous country. This contrasted with the religious conflict and near-constant warfare affecting 17th-century Europe.

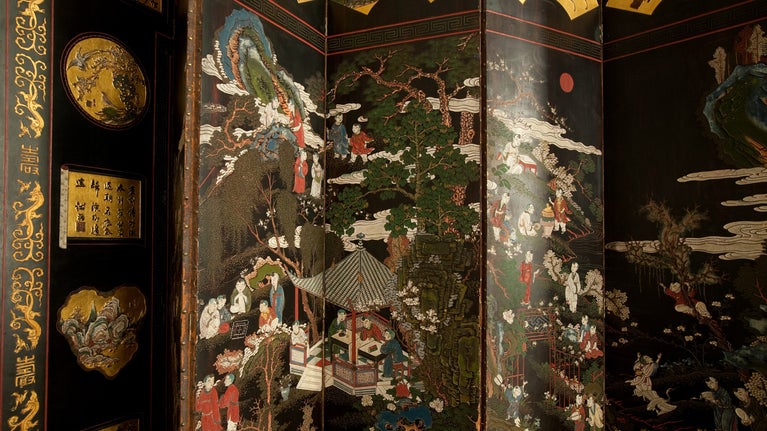

Apart from the bulk imports of Chinese tea, porcelain and silk, there were also smaller quantities of Chinese lacquer, paintings and prints being brought to Europe.

East India Company employees were allowed to import such things privately, sometimes sparking new consumer trends.

The late 17th century also saw the development of paper wallcoverings in Europe, as a cheaper alternative to tapestries and painted leather hangings.

As part of this trend, Chinese paintings and prints began to be used as 'wallpaper'. Specialist paper-hangers inserted them into gaps in the wooden wall panelling or used them to create wall-covering collages.

Until fairly recently, historians assumed that Chinese wallpaper was always entirely painted by hand.

But research into our collections has confirmed that the first Chinese wallpapers to be purpose-made for the European market, made around 1750, were in fact woodblock-printed, with colours added by hand.

Presumably, the European taste for Chinese prints gave Chinese printing workshops the idea to produce large, wallpaper-sized prints for the foreign market

There are examples of early woodblock-printed Chinese wallpaper at Uppark House in West Sussex, Felbrigg Hall in Norfolk and Ightham Mote in Kent. Up close, you can see tell-tale small breaks in the black lines that are common to woodblock printing.

Alongside purpose-made Chinese wallpaper, Chinese prints and paintings continued to be used as wallcoverings in the 1740s and 1750s.

The original meaning of these images was not well understood in Britain, but the cultural prestige that China enjoyed made them fashionable as interior design accessories.

Saltram, in Devon, is home to rare early Chinese wallpaper.

From the late 1750s, fully hand-painted Chinese wallpapers took the place of printed wallpapers. Several painters would work on each sheet, specialising in different elements such as architecture, rockwork, foliage and human figures.

There was a long tradition in China of painting birds and flowers. These motifs were also used on Chinese export wallpapers.

From about 1770, the Chinese painting workshops began adding brightly coloured backgrounds to their bird-and-flower wallpapers, probably designed to update their product and keep the European market interested.

The botanist Joseph Banks praised the Chinese wallpaper painters for what he saw as their scientific accuracy. But the presence of a mythical Chinese phoenix in the wallpaper at Nostell Priory (below) shows how Chinese artists were treating this scenery as a network of symbolic images, rather than a realistic copy of nature.

Individual birds and flowers had traditional symbolic meanings. A pair of ducks signified loyalty, pheasants were symbolic of beauty, peonies indicated fame and bamboo represented humility. These meanings were reinforced or refined when various motifs were combined.

Examples of Chinese wallpapers from the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th century show how the painting workshops continued to innovate. Designs for balustrades, bird cages and baskets of flowers were added to make scenes look even more like elegant gardens.

The 1790s saw the development of another type of wallpaper which combined human figures – based on genre paintings – along the bottom edge, with birds and flowers above.

There was less demand for Chinese wallpaper during the 19th century, but it was still used as part of high-end interior decoration.

By now, the taste for Chinese decoration was so ingrained in Britain that every grand country house was expected to have at least a few rooms decorated with Chinese wallpaper. These would generally be relatively private and informal rooms, like bedrooms, dressing rooms and drawing rooms.

Towards the end of the 19th century, historic Chinese wallpapers began to be bought and sold as antiques. Quite a few of them made their way to the United States. They were welcomed as exemplars of traditional Chinese art and European heritage chic.

Chinese wallpaper is a living tradition, a product of an ancient Chinese discipline that has been shaped and preserved outside of Asia by European and American tastes. The wallpaper on display at 18 historic houses in our care reveals a longstanding Western fascination with Chinese art and design over 400 years.

We care for one of the world's largest and most significant collections of art and heritage objects. Explore the highlights, our latest major exhibitions, curatorial research and more.

The 13,000 oil paintings in our care are nearly all displayed in the houses of their historic owners. Learn about the stories behind a selection of the artworks and their owners.

Discover how the use of paint in the historic interiors of four of the houses in our care reveals evolving fashions, new pigments and residents' wealth and status.

Learn about some of the misleading objects, paintings and architectural features in the historic houses we look after, and discover the truth behind these optical illusions.

‘The Mask of Youth’ gave Queen Elizabeth I ageless beauty in art. Read more about the history and where you can see examples in the collections in our care.