Our Conservation Story: Conserving the past, creating the future

A la Ronde has stood for over 200 years, and in that time has weathered south westerly storms, seen major building adaptations, been a family home, housed war-time evacuees, been divided into bedsits for tenants, and opened to visitors. Over the last few years, water leaking from the roof was damaging the Shell Gallery and Grotto Staircase.

Layers of paint were flaking away in the Octagon, and the Feather Frieze in the Drawing Room had become damaged and dirty with age. The National Trust has been caring for this unique and complex house since 1991 but of course the care is always ongoing. Urgent conservation and repairs were needed, which also gave us the opportunity to uncover and explore layers of history.

Conserving the 200-year-old Shell Gallery

A la Ronde and its contents need constant care. Recent water damage had left the Gallery vulnerable, and we needed to act quickly to save this special and important place. This gave us the chance to investigate the making of the decorations in more detail than ever before.

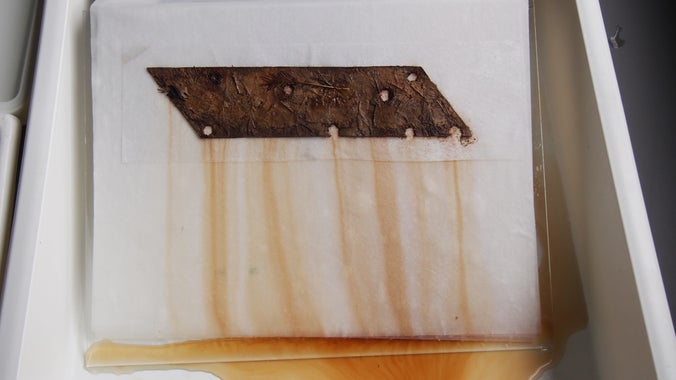

Specialist conservators repaired the historic plaster, secured each piece of decoration, and reattached hundreds of loose pieces. Paper and feather conservators cleaned the watercolours, bird panels, and feather decorations using soft brushes and sponges, and where safe, washed them to remove staining. Where the paper was torn or thin it was repaired, and new supportive backing papers were added.

Before the house was acquired by the National Trust in 1991, the Gallery had been opened to visitors with funds raised helping to ensure A la Ronde’s survival. Now the only visitors to this fragile space are conservators for monitoring and cleaning. Our collection team now carefully monitor and care for each element of the Gallery.

Lime plasters are made from recipes of prepared limestone and have been used for thousands of years. Adding sand and hair helps make the lime putty stronger and reduces cracking as it dries. Plastering and decorating the Shell Gallery would have taken skill, speed, and professional precision.

Feathers are naturally water resistant, so conservators were able to wash some of the Shell Gallery featherwork and their paper supports, shown here, to remove staining. Where the feathers were too fragile, soft brushes and sponges were used instead.

This puzzling piece of decoration was identified as a teapot spout made from Chinese porcelain with a metal tip. Research during conservation suggested it may date from as early as the 1650s, over 100 years before A la Ronde was built.

A temporary floor was installed, suspended between the Shell Gallery floor and the eight metre drop to the Octagon f loor below. This enabled a team of shell, paper, and plaster conservators to work safely on site.

Conservators research and study objects and spaces before work begins, often discovering how they were made or have changed over the years. This also ensures that planned and tested treatments care for the most important and significant parts of an object.

Conservators closely studied the way all the decorations were constructed, from the huge walls of the Octagon down to tiny details like this under drawing on a paper support in the Shell Gallery, revealed by lost shells.

We made an exciting discovery in one of the Shell Gallery bird panel collages. The eye of the parrot contains a fingerprint where the jewel has been pushed in. Could this belong to Mary or Jane Parminter, or perhaps a professional employed to make the decoration?

The Grotto Staircase

With light glinting from mirrors, glass, and gold paper quillwork, the Grotto Staircase winds up through the dark to burst into the light at the very top of A la Ronde. Specialist plaster conservators stabilised and repaired the areas of damage to the walls and cleaned the traces that many hands had left over the years.

Like the Gallery, the Grotto Staircase is decorated with shells, glass, lichen, mirrors and minerals, but it has a different design. It includes gothic arches, wall paintings, and two small grottoes. Arches have been used in religious architecture since medieval times, a design intended to create soaring heights pointing towards heaven.

The Grotto Staircase might have originally reached all the way to the ground floor. However, the lower part of the house was altered significantly in the 1800s by Reverend Oswald Reichel, so we don’t know for sure where the original lower flight of the staircase would have been.

200 years of use had caused damage to the plaster on the Grotto Staircase. Pieces of loose plaster were extremely vulnerable to crumbling away entirely. Conservators repainted the repairs to remain visible but to tone in with the colour of the wall paintings.

In one area, repairs to original nail holes were painted slightly lighter to show the echoes of an earlier handrail. Being able to see the new repairs helps us understand the original design of the staircase, and how it has changed over time.

The walls of the Grotto Staircase are painted with tall gothic arches pointing up to the sky, perhaps inspired by the architecture of the cathedrals and churches visited by Mary and Jane during their Grand Tour. The walls had become dirty and greasy from touch over the years.

Redecorating the Octagon

At the heart of the house, the walls and coving of the Octagon are over eight metres high. In this space, paint was flaking and being lost. We wanted to stop the damage and recreate the earliest known decoration more accurately.

Paint analysis showed the walls and coving were originally painted with distemper, in a scheme linked with the Shell Gallery ceiling above. Distemper is one of the oldest known types of paint. It is made from chalk or lime and has a matt finish that doesn’t bond well with modern emulsions.

Investigations in the 1990s had revealed that the oldest painted pattern was preserved under modern layers. In 2023, all the paint layers were stripped, and artists painstakingly recreated this pattern again. They used chalk-based paints with a matt finish similar to distemper, which will not flake off in the future.

While all the old paint needed to be stripped from the Octagon walls, a piece of the earliest known scheme was identified and preserved.

Artists used scaffolding to reach the top to recreate the hand-painted scheme. The complexity of the work suggests, as in other parts of the house, that Jane and Mary may have employed specialists to create this unusual design, possibly influenced by a popular textile pattern known as ‘flame stitch’.

Artists practised the technique needed to recreate the scheme by hand, before committing the paintbrush to the wall.

Thousands of Feathers

The makers of the Feather Frieze constructed it with skill, expertise and precision. Thousands of feathers have been arranged together in these symmetrical designs for over 200 years.

The circular ‘roundels’ contain feathers from native game birds and from species across the world. Conservators were able to identify parrot feathers using UV light, as well as peacocks, jays, guinea fowl, and waterfowl. Jane and Mary may have chosen these based on what was available to them, or to spark conversation amongst visitors to the house and show their wealth and fashionable tastes.

The feathers were originally stuck down with a kind of animal glue called isinglass, probably by professional crafts workers with great skill. The glue used is strong and durable but becomes brittle with age, so conservators used modern adhesives to secure weak areas. Feathers are made from protein which makes them delicious to pests like moths, and they are also delicate and easily broken.

Feathers have intricate structures known as barbs and barbules, which hook together to keep their shape. These can become unhooked and misaligned. It took conservators nearly 200 hours to treat the Feather Frieze, including using tiny brushes, tweezers, and other tools to realign individual feathers.

The Feather Frieze of A la Ronde may be a unique survivor of the fashionable and meaningful featherwork that once adorned the houses of other women in the 1700s. Feathers are fragile and easily damaged by pests, and this may be why so few examples have survived.

The Compendium

The Compendium is a collection of stories to delight and surprise. You can explore all things A la Ronde here in one central place for the first time. We will be adding new stories for years to come.

Our Project - A la Ronde: Conserving the Past, Creating the Future

In 2022 we embarked on a major project to transform A la Ronde’s offer for our visitors, volunteers, and local community.

Clocks and Pests: A day in the life of a Collections Assistant

Find out how the Collections Assistants at A la Ronde look after the house and its collections. From the many clocks to the smallest of its inhabitants: pests.

The Drawing Room

Bordered with an immaculately constructed feather frieze, the Drawing Room at A la Ronde tells us many stories about its history.